Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has dampened the global economic outlook, prompting predictions of spiralling price hikes not seen since the 1980s and looming recession. But, is it too soon to predict with any accuracy what really lies ahead? Professor Anthony Foley investigates.

After two years of economic uncertainty because of the pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and its associated sanctions, have unsettled our markets once again, lowering projected GDP growth rates and increasing global inflation rates in 2022 and, to a lesser extent, in 2023.

However, the exact scale of the impact is as yet uncertain. It will depend on several factors, including the duration of the conflict, developments in economic sanctions — both in terms of impositions on Russia and its own retaliative measures — and the nature of any possible peace deal.

Together, Russia and Ukraine comprise a relatively small part of the global economy, making up about two percent of GDP internationally. They are important players in the markets for certain products, accounting for about 30 percent of global exports of wheat, 20 percent of corn, roughly 20 percent of fertilisers, 20 percent of natural gas and 11 percent of oil.

Both countries also have substantial uranium reserves and are significant suppliers of the inert gases used to make semiconductors and the titanium sponge used in aircraft manufacturing.

On top of that, Russia is a major supplier of the palladium used in the catalytic converters for cars and the nickel used in batteries and steel, while Ukraine is among the world’s foremost producers of sunflower oil and sugar beet.

Mechanisms of the economic impact of war

There are several mechanisms through which war has an economic impact. Trade flows are suppressed, hitting integrated global supply chains. The rising cost of commodities like gas, fertiliser and oil upends business cost models and lowers real consumer income.

Even had there been no response from the rest of the world to the Russian invasion, Ukraine would still be unable to maintain existing supplies of products, such as wheat and minerals, to the global market. This alone would result in supply chain disruption and price hikes for certain products.

Uncertainty, in general, suppresses economic growth, muting confidence and lowering consumer spending and enterprise investment — and this is especially true of the current situation in Ukraine.

The intervention of the West thus far, through economic sanctions imposed on Russia and Belarus, has increased the economic impact of the war by limiting trade engagement with Russia.

Russia may retaliate against these sanctions by restricting gas supplies or defaulting on sovereign debt, which would further deepen the economic impact.

Energy prices were rising even before the Ukraine invasion, but the war has now accelerated the rate of inflation. Even if a country has no direct trade link with Russia, it will be affected by ongoing global price hikes.

Countries with trade links to Russia will have lower growth rates, curtailing their capacity to trade with other countries – even those with no direct trade links to Russia — triggering further global economic impact.

Hundreds of western companies have opted to cut business ties with Russia, even if not required by official sanctions, including big brand names like Coca-Cola, McDonald’s and Nike.

In addition, there are implications for the public finances of those countries taking refugees from and sending aid to Ukraine. If a peace settlement is reached, there will then be the cost of rebuilding Ukraine.

Irish trade with Ukraine & Russia

Ireland exported goods worth €627 million to Russia in 2021 (just 0.4% of its total exports) and imported goods worth €598.1 million from Russia. In the same period, goods exported to Ukraine totalled €91.7 million, while imports came to €70.2 million.

The imports of goods are dominated by petroleum and petroleum products (€231 million), coal and coke (€140 million) and fertilisers (€134 million). These three imports are 84 percent of total Irish imports from Russia.

The value of services traded with Russia is much higher, however. Ireland’s service exports to Russia were valued at €3,242 million in 2020 (i.e. 1.3% of total service exports). The value of services imported to Ireland from Russia in the same year was €360 million.

The main services exported to Russia were computer services (€1,840 million), operational leasing (€926 million), financial services (€81 million) and insurance (€27 million). The main service imports from Russia were business services. Service exports to Ukraine were €647 million in 2020, and imports were €49 million.

Impact on economic growth and inflation

There is significant uncertainty about the magnitude and duration of the economic impact of the war. However, the OECD, the National Institute of Economic and Social Research in the UK and the European Central Bank (ECB) have all recently attempted to quantify the economic impact.

The OECD estimates that in 2022, the war will reduce global growth by about one percent, from 4.5 percent to 3.5 percent. Global 2022 inflation will increase by 2.5 percent from 4.2 percent to 6.7 percent.

The Euro area economic growth will drop by about 1.4 percent from 4.3 percent to about 2.9 percent. Euro area inflation will increase from 2.7 percent to about five percent in 2022.

The estimated impact on the US is almost one percent off the growth rate and 1.5 percent on the inflation rate.

The assessment by the National Institute of Economic and Social Research in the UK is a little more optimistic but broadly similar to that of the OECD. Global growth this year may fall by 0.5 percent, while inflation could rise by about three percent.

Next year’s impact will not be as drastic, but it is something to watch out for. In 2023, we will see about one percent less in growth and an added two percent on the inflation rate. Euro area growth this year will fall by 0.9 percent, and inflation will rise from 3.1 percent to 5.5 percent. Euro area growth would be about 1.5 percent lower in 2023, and inflation would be about 0.8 percent higher.

Three economic scenarios

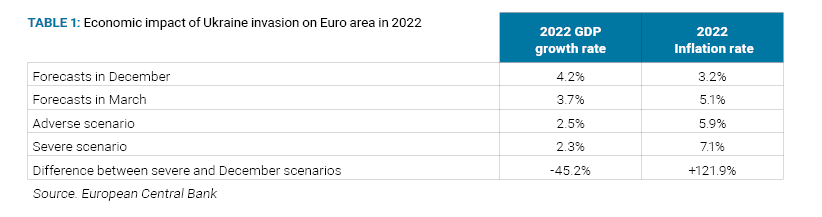

The ECB recently undertook a detailed analysis of the economic impact and presented three scenarios (Table 1).

In December 2021, the ECB forecast a GDP growth rate of 4.2 percent and 3.2 percent for the Euro area in 2022. These figures were revised in March, following the Russian invasion, to GDP growth of 3.7 percent and inflation of 5.1 percent.

This “baseline projection” assumes that current disruptions to energy supplies and suppressed confidence are temporary and that global supply chains are not significantly affected.

The ECB also produced forecasts based on two more negative but possible scenarios.

The adverse scenario assumes a worsening in all three impact mechanisms of trade, prices and economic confidence. The severe scenario assumes a more significant and prolonged increase in commodity prices, leading to second-round inflation and financial system impacts.

The differences between the severe scenario and the pre-war forecasts here are substantial. The growth rate drops by almost half from 4.2 percent to 2.3 percent, and the inflation rate more than doubles from 3.2 percent to 7.1 percent.

Of course, we do not yet know what the eventual impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine will be. We can be sure there will be lower growth, and inflation will rise. On the most extreme assumptions, growth could almost halve, and inflation could more than double compared with the forecasts for the Euro area before the invasion.

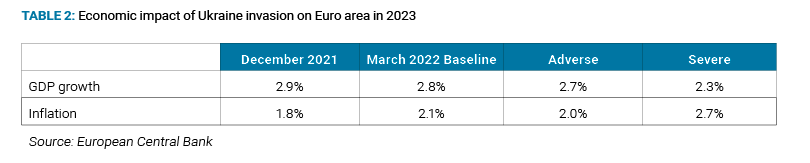

The ECB has also considered the potential longer-term impact of the Ukraine invasion on growth and inflation in the Euro area into 2023 (Table 2).

The news here is relatively positive, in that growth is closer to the ECB’s pre-war forecast of 2.3 percent on the severe assumptions, compared to 2.9 percent in December 2021. The same is true for inflation — 2.7 percent on the severe assumption compared to 1.8 percent in December 2021.

Possible economic impact on Ireland

Before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the economy was expected to perform well in 2022. The Stability Programme Update, published by the Department of Finance in April 2021, forecast GDP growth of five percent this year, followed by 3.5 percent in 2023.

Modified domestic demand was expected to grow by 7.4 percent this year and 3.8 percent next. Inflation was expected to be 1.9 percent in 2022 and 1.5 percent in 2023. Up until the invasion of Ukraine, this forecast was expected to be exceeded.

The forecasts underestimated the rise in inflation, however – the October 2021 budget forecast Irish inflation rates of 2.2 percent in 2022 and 1.9 percent in 2023.

Using the relativities of the severe ECB scenario, Ireland might face a growth rate of about 3.5 percent instead of around six percent in 2022 and inflation of eight percent instead of four percent.

The good news is that growth is still likely in Ireland and the Euro area because of the relatively high growth rates before the effects of the war.

Of course, particular sectors face a more daunting situation. Ireland’s aircraft leasing sector has high exposure to Russia, and it is uncertain how this will play out in terms of aircraft recovery.

International tourism was expected to rebound after COVID-19 in 2022, but the war may have a dampening effect, particularly in the case of US tourists. Many enterprises in Ireland have had to pause or end their business activities in, and trade contacts with, Russia.

Ireland must now cope with the financial requirements of taking in possibly 100,000 Ukrainian war refugees. However hard this may be, consider the position of Poland with millions of refugees to support.

The major immediate economic problem is the very high inflation rate to which the war has contributed but is not entirely responsible. How will consumers and producers cope with the price increases? To what extent can the Government shield households from the effects of rising energy prices?

It is already clear that the economic impact of the war is substantial, and the scale and duration of the impact are still unclear, but, as of now, we should be able to avoid recession.

Over the longer term, the economic impact will depend on whether there is a return to the pre-war normal (which is unlikely) and what the new normal will be in terms of trading blocs, continuing sanctions, higher defence spending, cyberwar, political tensions and bank payment systems.

Anthony Foley is Emeritus Associate Professor of Economics at Dublin City University Business School.

LOADING...

LOADING...